By Doerte Weig, Senior Researcher.

What might a San person or group have heard moving around the Daureb inselberg in Namibia around 4000 BP? Which kinds of sounds might they have made, gathering and hunting during the day, or singing and dancing during a night-time ritual? This is the question senior researcher Doerte Weig is exploring for the Artsoundscapes project.

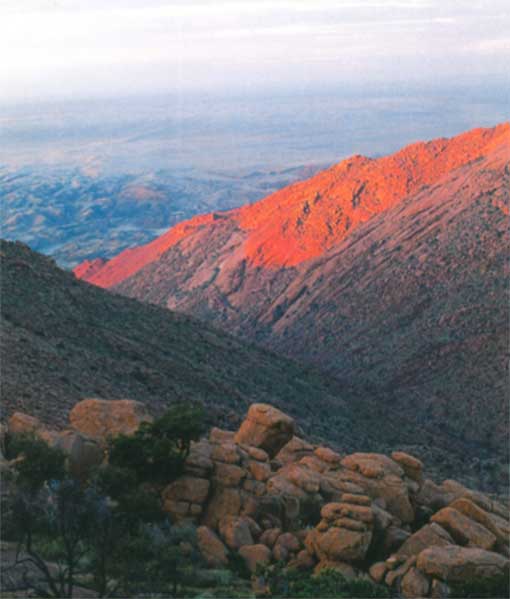

The Namibian Daureb in the south-western part of Africa, or as it is known internationally, the Brandberg, is a large round inselberg covering approximately 650 km2 and rising to 2,573m above sea level. It is known for its red colouring which is particularly striking given its setting in the midst of a large and nearly uninhabited landscape.

It is also known for its numerous high-quality fine line rock art sites, which were discovered for the European eye at the start of the 20th century and painstakingly documented in extraordinary detail by Harald Pager between 1977 und 1985. For many years now, Tilman Lenssen-Erz – the head of rock art research at the African Research Unit of the Institute of Prehistoric Archaeology at the University of Cologne and Artsoundscapes collaborator – has followed in and built on Pager’s work together with other colleagues in order to bring to light the wonders of the Daureb.

The red glow of the Daureb/Brandberg in Namibia (Lenssen-Erz & Erz 2000:9)

One of them is the remarkable Human Ethology Film Archive of the Senckenberg Gesellschaft fuer Naturforschung in Frankfurt (Germany). The archive holds and offers access to approximately 30 years of consecutive documentation on three Kalahari San groups, the !Ko, G/wi und the !Kung. In researching on archaeoacoustics, film sources are particularly interesting, as they allow the people themselves to speak and ‘sound’, to share what is known in anthropology as the emic perspective, peoples’ own view on things. My research stay at the ‘Human Ethology Film Archive’ offered me the chance to view films and stills, and hear sound materials as an entryway to specific San practices and the acoustic environments of Kalahari San lifeworlds.

The Artsoundscapes project studies the relations between acoustics and sacred practices. San healing dances are well-known and well-researched, for example, for their polyphonic singing style and how the practice of dancing-shaking enables healing of individual and group. San have an egalitarian social organisation that does not permit a special healer caste. Seeing and hearing the diverse film recordings at the ‘Human Ethology Film Archive’ helped me to start gaining a comprehensible, tangible, physical («embodied») insight into the different types of San ritual practices.

I was able to view the moving images of San healing dances and other San practices, such as hunting. Following the research goals of the Artsoundscapes project, the focus was on the sounds and noises that are created within the human community, as well as in relation to and in resonance with the various factors and conditions that make up the environment.

Doerte Weig searching for San sound experiences at the Human Ethology Film Archive in Frankfurt

Gathering information on possible acoustic contexts of prehistoric San at the Daureb is part of the broader shift within the archaeology and anthropology of rock art to give more detailed attention to the context, specificity and diversity of archaeological sites (David & McNiven 2018:4). It also highlights the premise that ‘one does not fully understand prehistoric art if one has not understood the space [and social context] around it’ (Lenssen-Erz 2008:13, 34; Deacon 1988). This can be recognized as including all information on acoustic environments and sound experiences.

The first year of the journey to discover what a San person or group might have heard moving around the Daureb inselberg in Namibia around 4000 BP, and what kinds of sounds a San group might have made, has been an exceptional one. From these initial steps, we have learned how music and ritual diversity pervade all aspects of San lives. For example, San used their hunting bows also as musical instruments, often even whilst walking through the bush (Vogels & Lenssen-Erz 2017). Ethnographic and ethnohistorical literature documents how San communicate with the people around them as well as receive communications from the landscapes they live in, in what has been called ‘landscape-cum-person communication’ (Widlok 2008) or !ore (Marshall 1976). This embedded, interactive relation to and with the environment seems to extend to rock art, which served also to mediate life and landscapes (Prada-Samper 2018). San practices of hearing-listening emerge as deeply embodied and multi-sensorial, refracting the ontological fluidity of San ways of perceiving the world.

These findings in more detail will soon be available as a peer-reviewed article. If you would already like to know more, please do not hesitate to contact Doerte Weig via our contact form or project email pr.artsoundscapes@ub.edu.

To can find out more about the Daureb rock art online, have a look at the website of the Arachne database, a free internet research tool for the Archaeologies, with an especially rich documentation of rock art sites from the Upper Brandberg.

[1] For the purposes of this text, we use the term ‘San’.

[2] A further constraining factor is that much literature on the San was written by missionaries and early settlers, who came with their own, often unfavourable lenses of interpretation of San practices.

Literature References

David, Bruno & McNiven, Ian J. 2018. Introduction: Towards an Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art, in David, Bruno & McNiven, Ian J. (eds.): The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art: Oxford University Press, 1–24.

Deacon, Janette. 1988. The power of a place in understanding southern San rock engravings. World Archaeology 20(1), 129–140.

De Prada-Samper, Jose M. 2018. I Have Already Seen in the Clouds»: The Nature of the Water-Creature Among the |Xam Bushmen and Their Modern Descendants. Фолклористика : часопис Удружења фолклориста Србије 3(1), 13–37.

Lenssen-Erz, Tilman. 2008. Space and Discourse as Constituents of Past Identities – The Case of Namibian Rock Art, in Domingo Sanz, Inés, Fiore, Dánae & May, Sally K. (eds.): Archaeologies of art: Time, place, and identity. London: Routledge, 29–50.

Lenssen-Erz, Tilman & Erz, Marie-Theres. 2000. Brandberg: Der Bilderberg Namibias. Stuttgart: Thorbecke.

Marshall, Lorna. 1976. The!Kung of Nyae Nyae. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Pager, Harald. 1989–2006. The Rock Paintings of the Upper Brandberg. 1989: Volume I., 1993: Volume II., 1995: Volume III., 1998: Volume IV., 2000: Volume V., 2006: Volume VI. Cologne: Heinrich-Barth-Institut.

Vogels, Oliver & Lenssen-Erz, Tilman. 2017. Beyond individual pleasure and rituality: Social aspects of the musical bow in southern Africa’s rock art. Rock Art Research 34(1), 9–24.

Widlok, Thomas. 2008. Landscape unbounded: space, place, and orientation in ≠Akhoe Hai//om and beyond. Language Sciences 30(2-3), 362–380.