The Site

The Greco-Roman city of Oxyrhynchus was surrounded by a fortification wall that can still be made out on the west side of the city, which faces the desert. The wall, made of mud brick, has been lost on the north and south sides of the city. However, it is possible to gain a reasonably good idea of the extent of the city. On the east side, the most notable landmark is a monumental stone gate, Pharaonic in appearance, which stands between the current city of El-Bahnasa and the Bahr Yussef. Using these landmarks, Oxyrhynchus as a whole appears to have measured 2 km north-south by 1.5 km east-west, while its population is estimated at potentially 30,000 inhabitants.

In the Roman period, when the city grew to its greatest size, the fortification wall enclosed a series of neighbourhoods organized around a large central necropolis, which we have named the Upper Necropolis. A large temple, possibly dedicated to Serapis, rose in the centre of the Upper Necropolis and a sizeable market stood opposite. The city had one central artery running north-south, with two large intersecting avenues running across the northern and southern halves of the city. The northern avenue connected the market and the temple of the Upper Necropolis with the central artery and the southern avenue connected the theatre with the Bahr Yussef, passing the tetrapylon of Taweret and the monumental East Gate. In the Pharaonic period, the population probably clustered in the vicinity of the tetrapylon and the baths were located to the south.

An Osireion is located to the west of the walled enclosure of the city. The surviving subterranean part of the Osireion basically dates to the Ptolemaic period. Between the Osireion and the city is a Greco-Roman necropolis.

In the Christian-Byzantine period, a number of monasteries for monks and for nuns were built outside the city walls. This information, which comes to us through an anonymous, contemporary Greek text, has been confirmed by our own excavations at a large fortified villa to the northwest of the city and a Coptic Christian oratory nearby. Further confirmation comes from the emergency excavations of Egypt’s Ministry of State for Antiquities to the south of Oxyrhynchus, where the remains of another monastery have been unearthed.

The mission’s work began with the continuation of excavations on the necropolis started in 1982. The mission examined all of the funerary structures already unearthed by Egyptian archaeologists in the necropolis, which has subsequently been named the Upper Necropolis. Among the structures studied, tomb no. 1 is particularly noteworthy because it was constructed during the Saite period and survives practically intact. The tomb has a complex layout and is built of well-hewn and arranged blocks of white stone. The tomb’s chambers are covered by barrel vaults. As a family tomb, the structure contains anthromorphic stone sarcophagi that are covered in hieroglyphic inscriptions and were used for the burial of an entire family of high priestly officials, possibly between the seventh and sixth centuries BC. Subsequently, the mission found and excavated other tombs of the Saite period, most notably tombs no. 13 and 14, which reflect similar construction techniques. Tomb no. 14, the largest tomb found to date, was partly destroyed in antiquity, but it was, in all likelihood, expanded in later periods. One of its naves, covered with a barrel vault, probably has the greatest span of any Egyptian Pharaonic architecture known to date. The excavations have unearthed a significant funerary deposit and the hieroglyphic inscriptions identify up to three generations of priestly officials and their families. The Saite-period inscriptions in tomb no. 14 and tomb no. 1 document the existence of the cult of Taweret; give the Pharaonic name of the city, Per-Medjed, which predates Oxyrhynchus; and name the sanctuary itself as Per-Khef.

In the vicinity of the Saite-period tombs, many other tombs from the Greco-Roman period have been unearthed. In general, they are smaller and make use of smaller hewn blocks of stone. Interestingly, however, they imitate the construction techniques of the Saite period, particularly in the use of relatively complex structures and the presence of chambers covered by barrel-vaulting. Although many of the tombs have suffered looting since antiquity, recent findings include significant funerary deposits and a large number of mummies covered with ornately decorated cartonnage. Some tombs have short inscriptions in Greek carved in their walls, while others feature wall paintings or reliefs with mythological and funerary scenes, particularly depictions of the oxyrhynchus fish, also first documented in the city that bears its name.

For many years, scholars were aware of the large number of bronze statuettes depicting the oxyrhynchus fish, and their suspicion was that these came from the city of Oxyrhynchus. It turns out, however, that this suspicion was wrong. As Oxyrhynchus was consecrated to the god Seth, who murdered his brother Osiris, the oxyrhynchus fish was believed to be the Seth animal that devoured the penis of Osiris when Osiris’ body was quartered and thrown into the river. The recent finds of bronze statuettes with a dedication to Taweret, however, have shown that the oxyrhynchus fish, a feminine noun in Classical Egyptian, is actually the sacred animal of the goddess Taweret, the supreme deity of Per-Medjed. Greco-Roman tombs in the Upper Necropolis, the source of these statuettes, have helped to demonstrate this link between the oxyrhynchus fish and the goddess Taweret.

The Greek population of Oxyrhynchus maintained their mother tongue, but adopted Egyptian funerary rites and gods. The most important deity was Serapis, a healing god and the Greek version of the native Egyptian god Osiris-Apis. Presumably, the temple of Serapis, the Serapeum, was located in the centre of the city. Recently, within the archaeological site, the mission has found the remains of a large temple from the Classical period in very poor condition. Excavation continues, but it is highly likely that the structure is the Serapeum. It is anticipated that future campaigns will serve to confirm or disprove this hypothesis.

The inhabitants of Oxyrhynchus converted to Christianity throughout the fourth century AD, but continued to use the site of the Upper Necropolis as a burial grounds. In this vein, the mission has found significant funerary structures built over or re-using Greco-Roman tombs. These structures are made of mud bricks, but they often have important wall paintings and inscriptions in Greek that are Christian in nature and have had to be removed from their support and restored. Some of these tombs were individual, while others were for groups.

Most of the urban remains of the city have been razed to the ground. Only the ruins of a few monuments remain identifiable. As a result, before the mission began excavations in 1992, practically the only source of knowledge about the city came from papyri. Papyri provided fascinating information about the daily life of the residents of Oxyrhynchus. In fact, Oxyrhynchus was one of the cities in the Roman Empire about whose daily life and routines the most was known. By contrast, knowledge of its topography and urban development was scant. For this reason, one of our first guidelines was to study the ancient urban plan of the city.

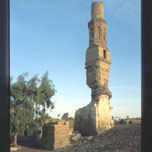

This study involved the use of various methodologies at our disposal: archaeological prospecting and surveys; radar; kite aerial photography; topographical indications from the papyri; and the documentation of drawings, maps and photos of the site building on Denon’s work from the nineteenth century. It seems likely that the ancient (Pharaonic) centre of the city was located toward to the southeast of the site, between the monumental East Gate and an honorific column that survives. The column was dedicated to the emperor Phocas (602-610 AD), who also had an honorific column in Rome, the last civil monument erected in the Roman Forum. The column in Oxyrhynchus, however, formed part of a tetrapylon, a monumental intersection that would have been found near the Thoereion, the temple of Taweret. We also know the location of the theatre, to the southwest; the location of some baths, to the south; and the location of a hippodrome, to the north. However, extremely few visible remains survive to the present day. We also know of the existence of several temples that remain hard to locate at present.

The enclosure of the Upper Necropolis stands near the centre of the northern half of the city. When it opened in the Saite period, the Upper Necropolis was some distance outside the city. With later urban growth, however, the city expanded to encompass the burial grounds. As we have seen, the site continued in use as a necropolis in Greco-Roman and Christian periods. Also, in the Greco-Roman period, a large temple was built there, possibly a Serapeum.

Headed due west from the temple built within the Upper Necropolis, we come to a small elevation of land, at a distance of approximately 1.5 km. This is the Osireion, a subterranean temple dedicated to Osiris. The temple has a series of galleries or catacombs dug into the rock. It has one principal entrance and two secondary entrances. One of the galleries contains a prone statue of Osiris, measuring more than three metres in height. Some of the galleries also contain a series of niches built into the walls on both sides, for the burial each year of an earthen statuette of Osiris that had been the principal object of the mystery rite of the god’s resurrection in the previous year. We know that this type of temple existed in other places in Egypt, but the Osireion of Oxyrhynchus is currently a unique monument due to its unique state of preservation.

The lintels of the niches bear a series of hieratic inscriptions that provide corroborative data on the burial of each statue. The inscriptions extend from the reign of Ptolemy VI Philometor to the joint reign of Ptolemy X Soter II and Cleopatra III. All of these dates correspond to the second half of the second century BC. In addition, the inscriptions provide the name of the temple, Per-Khef. Thanks to the hieroglyphic inscriptions in the Saite tombs in the Upper Necropolis, we know that this temple, Per-Khef, already existed in the Saite period.

The exterior part of the temple is completely demolished, although the rectangular outline of the temenos surrounding the sacred enclosure survives. When the mission discovered the Osireion and began work in 2000 and 2001, the researchers found that the name Per-Khef had already appeared on blocks of stone surfacing on the antiquities market in the nineteen-fifties. Today, some of these blocks are housed in museums in Leiden (the Netherlands) and Besançon (France), while the majority reside in private collections in Switzerland. The reliefs on these blocks depict divine triads in which Taweret appears in the form of a woman, as a secondary divinity associated with Osiris. The inscriptions mention the name of the temple, Per-Khef, and the names of the kings Alexander IV of Macedonia, who was the son of Alexander the Great; Ptolemy I Soter, and Ptolemy II Philadelphus. This makes it clear that the Osireion of Oxyrhynchus was the object of restoration work in the time of the early Ptolemies. It also appears that the superstructure of the temple was dismantled by looters who sold the blocks of stone on the antiquities market.

However, the surprises do not stop there. When the mission excavated a large fortified villa from the Byzantine and Arab periods, located not far from the Osireion, researchers found numerous reused blocks of stone with Coptic decoration that also bear fragments of inscriptions and reliefs similar to the ones in Per-Khef. It is therefore likely that the superstructure of Per-Khef began to be dismantled in the Byzantine period.

The large fortified villa has a series of outbuildings related to Christian worship, suggesting that it became a monastery for monks at some time, one of many monasteries erected in the vicinity of Oxyrhynchus in the Coptic period. In any event, the place was occupied after the Arab conquest. The finds include an Arab inscription from the seventh century, as well as a tombstone with an inscription from the reign of the emperor Diocletian, which also gives a date toward the end of the seventh century.

Near the villa or monastery, which is located to the northwest of the city, we have also found a hermitage with important Coptic inscriptions; a little treasure of 600 coins from the fourth and fifth centuries AD; a votive altar from around the first century BC, which could bear some relation to the overland route north out of the city; and a bird necropolis and an underground quarry. The rest of the land between the west wall of the city and the Osireion is occupied by an extensive Greco-Roman necropolis.

Lastly, to the south of Oxyrhynchus, emergency excavations carried out by Egypt’s Ministry of State for Antiquities have found yet another monastery.