|

/INTRODUCCIÓN

During the two centuries which transpired between the beginning of the 1500s and the early 1700s, the Kingdom of Naples was a possession of the Spanish Empire ruled by powerful viceroys who behaved, by right and de facto, as the monarchs’ alter ego.

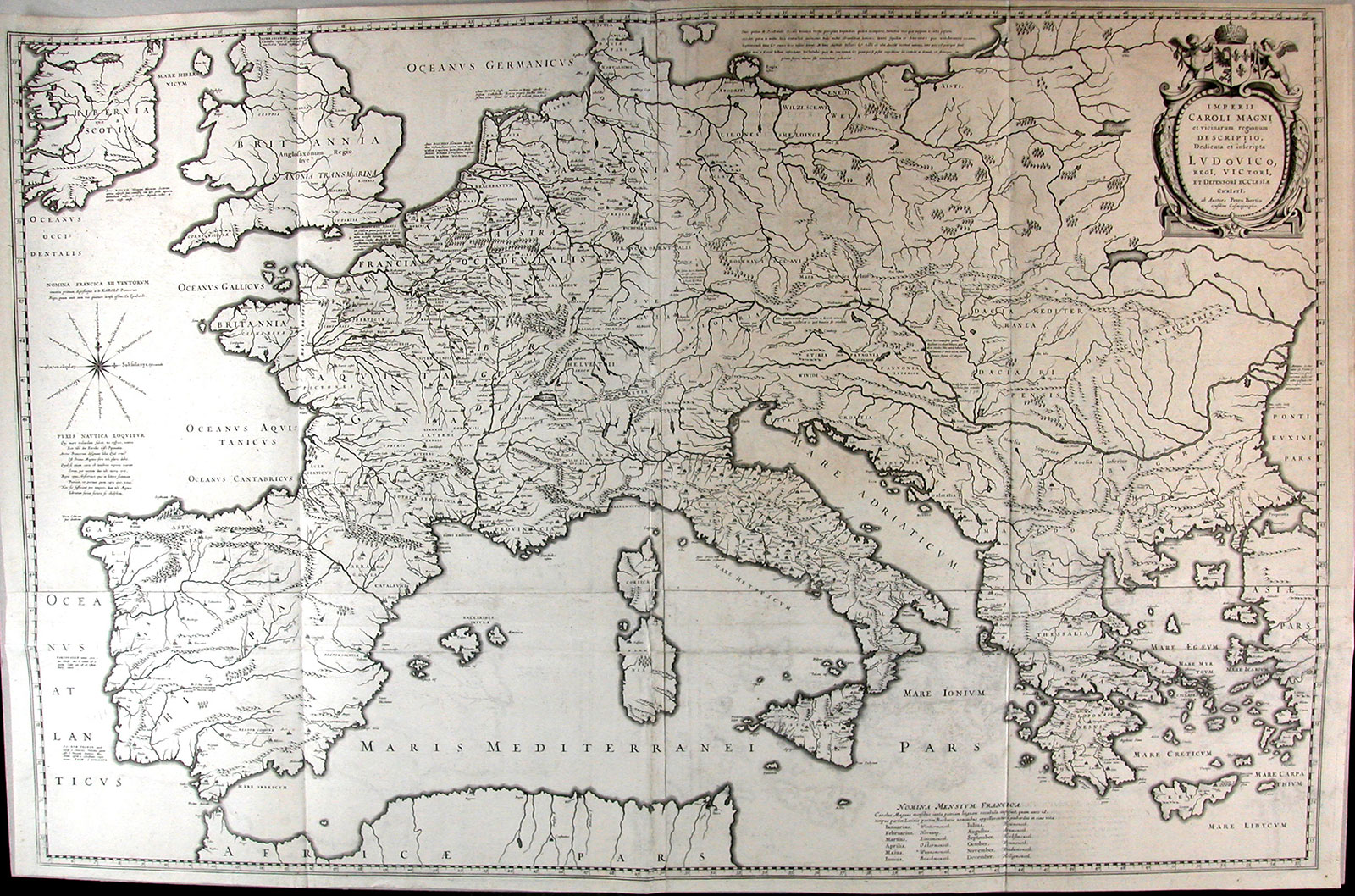

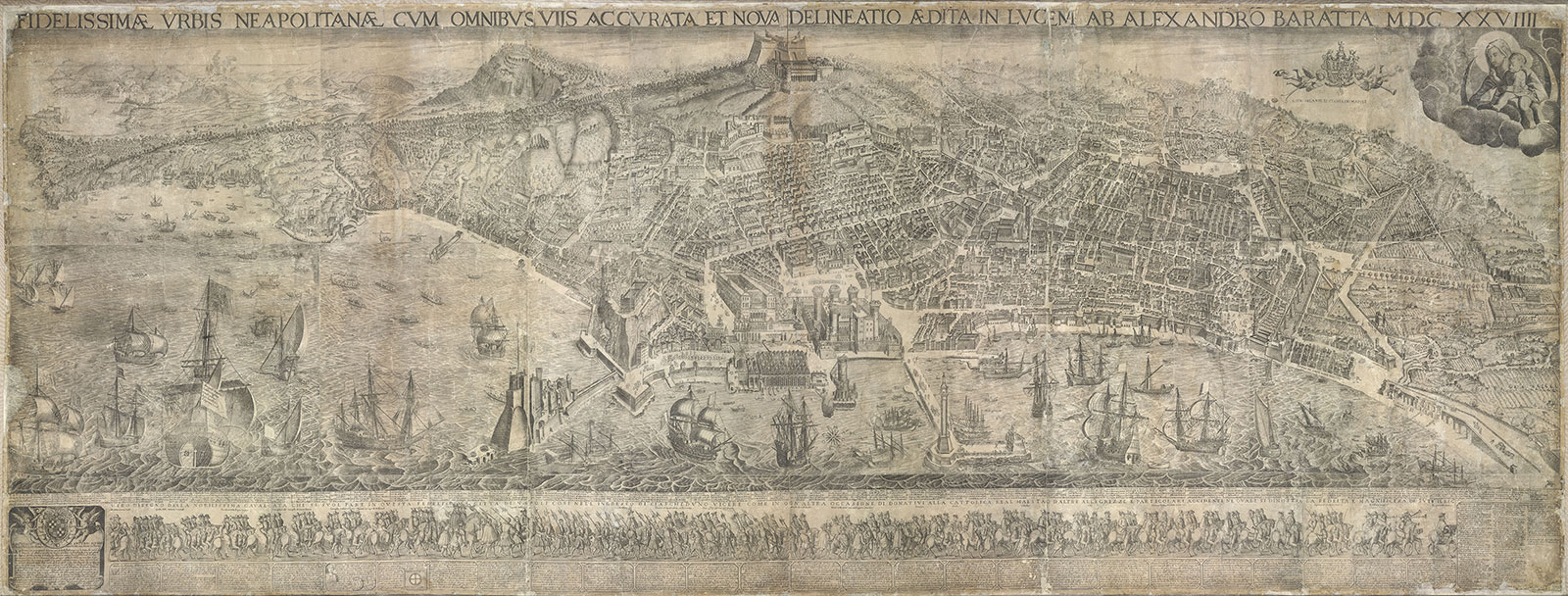

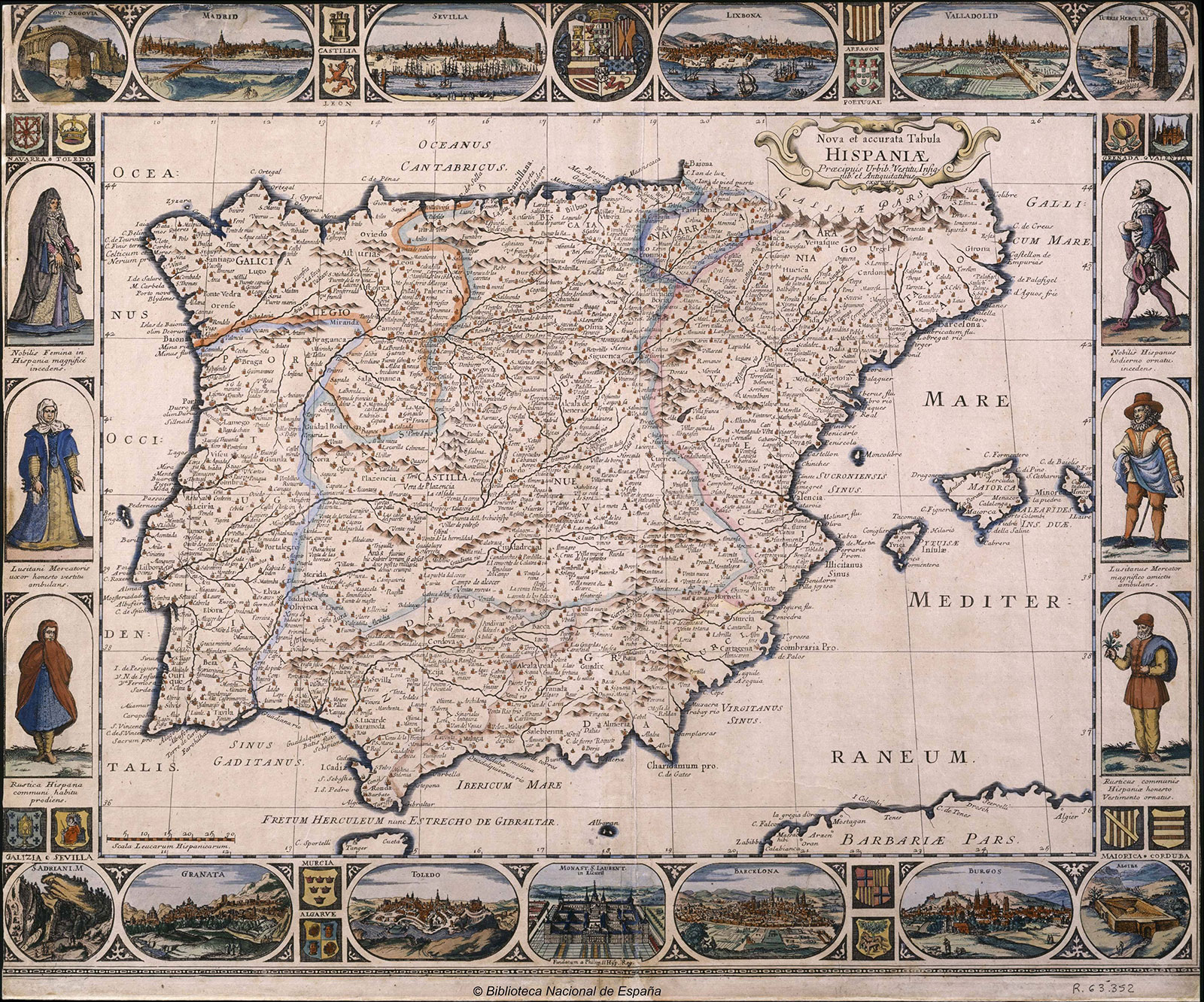

Following the unification of Italy (1861), historians tended to consider the viceroys’ rule as the root of Mezzogiorno’s principal problems. This vision has changed in recent decades, in which scholars have highlighted the complexity and diversity of the problems with which the viceroys had to contend. The multimedia project Sguardi Incrocciati focuses on one of the most visible dimensions of the viceroys’ rule: their activity as patrons of art and culture. The majority of these viceroys were members of the high Castilian nobility, creating, in Naples, one of Europe’s most splendid courts, which aspired to compete with those of the Roman pontiff and even the King of Spain. The results of this activity can still be perceived, in the urbanism and architecture, civil and religious, in both the capital and the key cities of the provinces. Its consequences reached – and had a remarkable impact – as far as Spain itself. Indeed, at the end of their stay in Naples the viceroys took with them a great quantity of works, such as paintings, sculptures, furniture and books, which they had acquired (at times through means of dubious morality) in the city. Thanks to them, Naples became, in many senses, the true cultural centre of the Hispanic Monarchy. Many of these pieces came to form part of their private collections. On returning to Madrid or to their home towns, many viceroys built dedicated galleries to exhibit them in their palaces. But their lavish lifestyles meant that on no few occasions they, or their heirs, were forced to sell them in order to settle their numerous debts. As a result, many collections soon became dispersed, with the works of Neapolitan artists ending up in the most unexpected places. In other cases, the pieces the viceroys sent to Spain were destined for churches and convents under their direct protection. A number of these, even today, represent true Neapolitan microcosms embedded in the heart of the Iberian Peninsula. The viceroys, however, worked not only on their own collections. One of the missions expected of them was that they would contribute to fulfilling the monarchs’ insatiable thirst for works of art. In some cases, they did so through valuable gifts with which they hoped to obtain some manner of recompense. In others, they acted on the express instruction of their masters, who charged them with procuring works by the most renowned Italian artists with which to decorate their residences. This latter took place most noticeably during the 1620s and 1630s, at which time King Philip IV was building his recreational palace, the Buen Retiro, on the outskirts of Madrid. In this manner, the Italian aesthetic contributed enormously to creating the public image of the Spanish Monarchy. For the majority of the viceroys, Naples was the final stage of a lengthy journey. On their route towards the kingdom’s capital, many of them carried out a tour of the Italian peninsula, which frequently began in Genoa, occasionally passed through Florence and Venice and almost always involved an important stay in Rome. In fact, before serving the monarchy as viceroys of Naples, many had previously done so as ambassadors to the Holy See. In Rome they had the opportunity to meet some of the most celebrated Italian and European artists of the day and to be infected by the climate of visual effervescence characteristic of the Counter-Reformation. To reflect the intensity of this circulation of works of art that the viceroys propelled, between Italy and Spain, the project Sguardi Incrociati has been designed as a two-way journey. Through diverse maps and plans, we have attempted to indicate the various sites in which their activity as patrons was evident. Although the viceroys admired the work of the foremost Italian artists – and, indeed, enthusiastically acquired it – their attitude was not merely passive. Many of them were expert connoisseurs with refined tastes and a very specific idea of what they wished to obtain. Their patronage, therefore, was the result of the intersection between their expectations as patrons and the possibilities of formal language offered by Italian artists, hence the title of this project: Sguardi Incrocciati. This multimedia project has been carried out by the research group “Poder i Representacions” of the Universitat de Barcelona, in the framework of the European ENBACH project (European Network for the Baroque Cultural Heritage), coordinated by Professor Renata Ago of Rome’s Università “La Sapienza”. The composition of the 150 files which make up the current project has involved the collaboration of 36 scholars of diverse nationalities, among whom are teachers and researchers from five different European countries. |

|

Church

Palaces

Monument

Ceremony

Musical

Royal houses

|

|

Palermo

|

|

Barcelona, the Viceroys’ Port of Arrival and Departure

|

|

Milan

|

|

Genoese Stopovers in the Journeys of Pascual and Pedro Antonio de Aragón (1661 and 1662)

|

|

Spanish Cagliari

|

|

Roma

|

|

Reino de Nápoles

|

|

The Viceroys of Naples in the Holy House of Loreto

|

|

Spanish Collectionism in Venice

|

|

The Courts of Florence and Urbino and Diplomatic Gifts for the Viceroyal Court of Naples

|

|

The Voyages of the Count of Monterrey

|

|

|

|

Church

Palaces

Monument

Ceremony

Musical

Royal houses

|

|

Church and Monastery of San Francesco di Paola ai Monti

|

|

Piazza di Spagna, Space of Representation

|

|

The Palazzo dello Spagnolo

|

|

San Giacomo degli Spagnoli

|

|

The Ceremony of the Acanea or Chinea

|

|

The Festival of the Resurrección in Piazza Navona

|

|

Pedro Antonio de Aragón’s Embassy of Obedience to Clement X in the Papal Residence of Quirinale (1671)

|

|

Church of San Pietro in Montorio

|

|

Santa Maria di Monserrato

|

|

La archicofradía del Spirito Santo dei Napoletani

|

|

|

|

Church

Palaces

Monument

Ceremony

Musical

Royal houses

|

|

Nápoles

|

|

Gaeta, Port of Entry

|

|

Procida and Ischia

|

|

The Baroque Ceiling of the Basilica di San Nicola in Bari

|

|

Lecce

|

|

The Convento di San Domenico di Soriano Calabro

|

|

The Viceroys and Montevergine in the Seventeenth Century

|

|

The Statue of Charles II in Avellino (1668)

|

|

L' Aquila

|

|

Pozzuoli: A Meeting Point for the Court, a Stone’s Throw from the Capital

|

|

Taranto and the Dioceses under Royal Patronage

|

|

Church

Palaces

Monument

Ceremony

Musical

Royal houses

|

|

Santa Lucia al Monte

|

|

Largo di Palazzo, the Backdrop to the Viceroyal Celebrations

|

|

Royal Cavalcades in Viceregal Naples

|

|

Baroque Fountains

|

|

Church of San Giacomo degli Spagnoli in Rome

|

|

The Torrione del Carmine and Masaniello’s Revolt

|

|

Churches of the Spanish Religious Orders in Naples

|

|

The Convento di Santa Maria Maddalena delle Convertite Spagnole

|

|

The Ospedale di San Gennaro dei Poveri

|

|

The Duke of Traetto’s Villa: a Stage for Posillipo’s Festivities

|

|

Palazzo Vecchio

|

|

The Music Chapel of Pio Monte della Misericordia

|

|

A Near-Perfect Real Sitio: The Villa of Poggioreale and its Surroundings

|

|

Santa Maria della Solitaria

|

|

The Music Chapel of San Giacomo degli Spagnoli

|

|

The Immacolata Concezione di Suor Orsola Benincasa

|

|

Procession of the “Ottava del Corpus Domini” or the “Quattro Altari”

|

|

The Port and Private Harbour of Naples

|

|

Teatro di San Bartolomeo

|

|

Port’Alba and the Seventeenth-Century Gates

|

|

The Royal Vault in the Monasterio di San Domenico Maggiore

|

|

Regi Studi

|

|

Santa Maria del Pianto

|

|

Caresana’s Tarantella, Musical Emblem of Naples

|

|

The Good Friday Procession of La Solitaria

|

|

España

|

|

Palazzo reale de Nápoles

|

|

The Chiesa e Convento di Santa Maria Egiziaca

|

|

La cavalcata della vigilia di san Giovanni Battista (23 giugno)

|

|

Palazzo Donn’Anna

|

|

El nacimiento de la Riviera di Chiaia

|

|

San Francesco Saverio (hoy San Ferdinando)

|

|

Capilla del Tesoro de San Genaro

|

|

Santa Lucia al Monte

|

|

|

|

|

|

Church

Palaces

Monument

Ceremony

Musical

Royal houses

|

|

The Masters of Ceremony of the Palazzo Reale di Napoli

|

|

The Gardens of the Palazzo Reale

|

|

Palatine Chapel, Royal Musical Chapel

|

|

Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725): a Maestro di Cappella

|

|

La Sala d'Ercole, antigua Sala dei Viceré

|

|

The Facade of the Palazzo Reale di Napoli

|

|

The Palatine Chapel

|

|

La galería

|

|

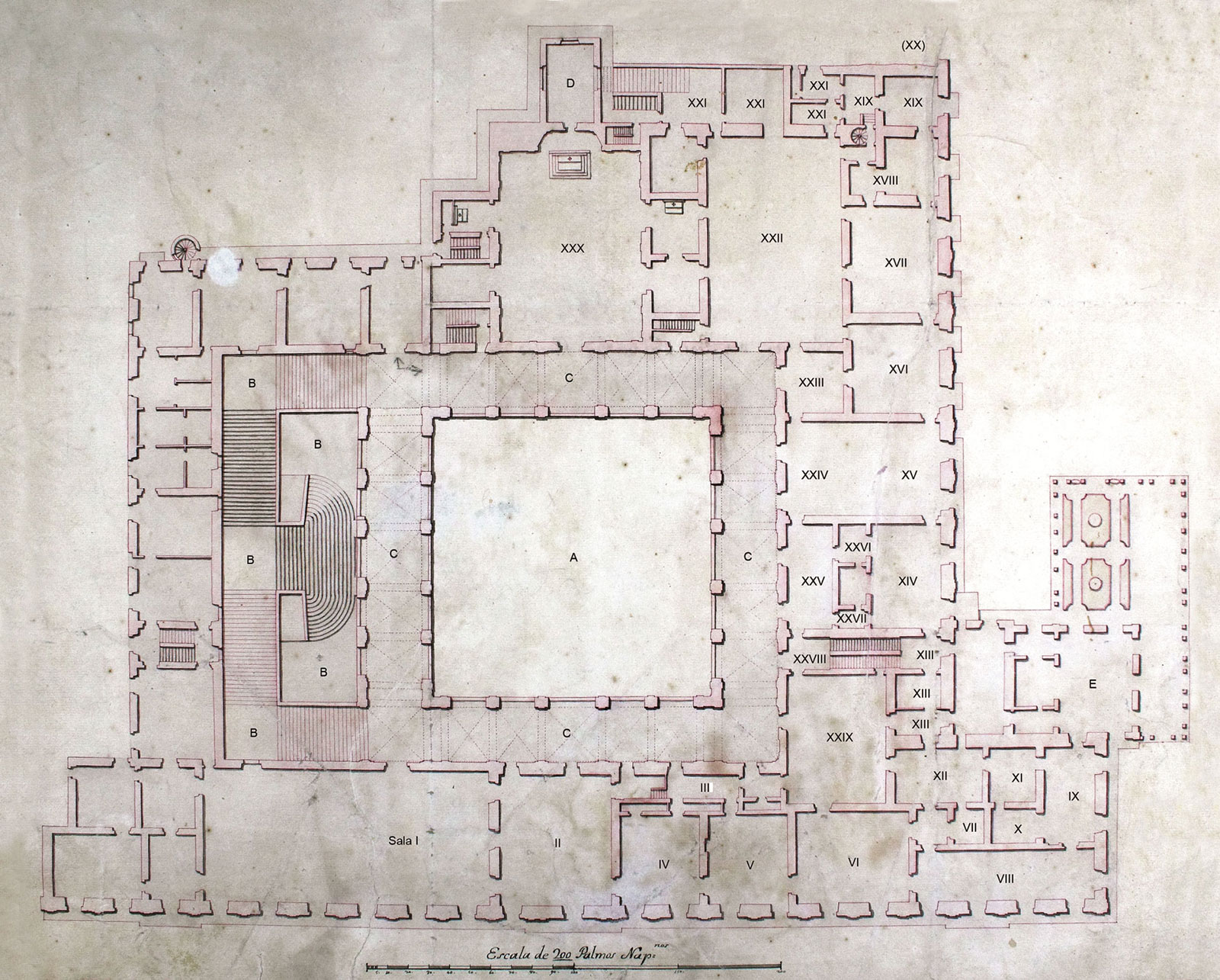

The Palazzo Reale

|

|

Sala regia o teatrino di corte

|

|

Teatro de corte

|

|

La escalera monumental

|

|

Las pinturas de los salones

|

|

Los salones y el appartamento di rappresentanza

|

|

|

|

Church

Palaces

Monument

Ceremony

Musical

Royal houses

|

|

The Convento de Monforte de Lemos (Lugo)

|

|

The Castillo de los Condes de Benavente

|

|

La Inmaculada Concepción de monjas agustinas recoletas de Salamanca

|

|

Convento de Peñaranda de Bracamonte (Salamanca)

|

|

Toledo’s Convento de la Purísima Concepción

|

|

The Convento de San Diego, Valladolid

|

|

Lerma’s Convento de San Blas

|

|

Neapolitan Sculptures in Salamanca’s Convent of Augustinian Recollects

|

|

Catedral de Toledo

|

|

Luca Giordano in Aranjuez

|

|

Madrid

|

|

La Casa de Pilatos de Sevilla

|

|

Monasterio del Milagro de Cocentaina

|

|

The Monasterio de Poblet

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Church

Palaces

Monument

Ceremony

Musical

Royal houses

|

|

The Jardín de San Joaquín

|

|

The Palace of the Counts of Oñate

|

|

The Palacio del Buen Retiro and its Decoration

|

|

The Palace of Pedro Antonio de Aragón

|

|

Convento de Santa Teresa de Jesús

|

|

Santa Isabel

|

|

Matteo Sassano detto Matteuccio, "il rosignolo di Napoli"

|

|

Francesco Paolo Capoccio, Neapolitan Violinist in the Capilla Real of Charles II

|

|

The Neapolitan Sculptures of the Congregación del Santo Cristo

|

|

San Antonio de los Alemanes (or “de los Portugueses”)

|

|

La huerta de Recoletos

|

|

Las esculturas napolitanas de la Congregación del Santo Cristo

|

|

El Alcazar de Madrid

|

|

El altar de pórfido de la capilla real del Alcázar

|

|

La pintura napolitana en las colecciones reales

|

|

El palacio de los VI condes de Monterrey en el Prado Viejo de San Jerónimo de Madrid

|

|

|

|

/VICEROYS

Browse the gallery and discover the biographies of the 28 viceroys and lieutenants who ruled the Kingdom of Naples in the seventeenth century.

|

|

|

1598

|

|

1599

|

|

1600

|

|

1603

|

|

1607

|

|

1615

|

|

1617

|

|

1618

|

|

1621

|

|

1622

|

|

1625

|

|

1627

|

|

1630

|

|

1631

|

|

1634

|

|

1635

|

|

1636

|

|

1640

|

|

1643

|

|

1644

|

|

1646

|

|

1647

|

|

1648

|

|

1649

|

|

1650

|

|

1652

|

|

1655

|

|

1656

|

|

1657

|

|

1658

|

|

1659

|

|

1661

|

|

1662

|

|

1664

|

|

1665

|

|

1667

|

|

1668

|

|

1670

|

|

1673

|

|

1674

|

|

1675

|

|

1676

|

|

1679

|

|

1689

|

|

1692

|

|

1696

|

|

1697

|

|

1700

|

|

1702

|

|

1707

|

|