World Oceans Day: Seabirds and the Network of Marine Protected Areas

June 8th, 2020

The seas and oceans are one of the most unknown and at the same time most fascinating ecosystems on the planet. However, growing human activities in the marine environment are rapidly accelerating their deterioration. As a result, many countries are increasing the surface of their marine protected area. In Spain, the figure of Marine Protected Area has existed since 2007 (Law 24/2007 on Natural Heritage and Biodiversity), and in 2010 the Network of Marine Protected Areas was formally created (RAMPE, law 41/2010 on the protection of the marine environment) with the aim of carrying out a coherent management of the marine environment in order to achieve its good environmental status. In 2014, 39 special protection areas for birds from the Natura 2000 Network became part of the RAMPE. Despite this, only around 13% of Spanish waters are currently under some form of protection, and many of them still do not currently have management plans that take into account such important aspects as interactions between seabirds and fishing or aquaculture.

Seabirds are top predators, meaning they are found in the upper levels of marine trophic networks. This advantageous position makes them sensitive to most alterations in the marine ecosystem, making them sentinel species of the seas and oceans health. In addition, seabirds live at the interface between the marine and terrestrial environments, feeding at sea and returning to land to rest, nest and rear their chicks, allowing us to study them with relative ease. One of the most important information we can get from seabirds is their at-sea distribution, the areas they use to feed and to find food for their chicks. This information, combined with diet and ecotoxicology studies helps us to know the environmental quality of the different marine regions, as well as the health of fishing stocks. The most practical and accurate method for obtaining this information is the deployment of remote tracking (GPS) devices, which can record and transmit their movements at intervals of up to less than a minute through the mobile phone network.

Currently, our research group (Seabird Ecology Group) of the Faculty of Biology and the Biodiversity Research Institute (IRBIo) of the University of Barcelona, in collaboration with the Association of Naturalists of the Southeast (ANSE), are developing two projects with the support of the Fundación Biodiversidad from the Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge, and also in collaboration with the Spanish Institute of Oceanography (IEO). The objectives of both projects are linked to the actions of LIFE INTEMARES, which pursues the effective management of marine areas within the Natura 2000 network, with the active participation of the involved sectors and research as basic tools for decision making.

The project "AMARYPESCA: Seabirds as an instrument for improving fisheries and aquaculture management in the context of a sustainable RAMPE", in the framework of the 2019 call of the Pleamar Program, co-financed by the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund, aims to knowing the role that the current RAMPE plays in the conservation of seabirds, in addition to investigating the interactions between seabirds and fishing and aquaculture activities, in order to improve the management of RAMPE and human activities at sea.

Along the same lines, the project "GAUDIN: The Audouin's gull as an instrument for improving the management of RAMPE in Spain’s east coast", in the framework of the call for proposals for the conservation of marine biodiversity in Spain 2019 of the Fundación Biodiversidad of the Ministry for Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge, seeks to know the role of the current RAMPE in the conservation of Audouin's gull (Ichtyaetus audouinii) and characterize the interactions between these birds and fishing vessels.

To achieve these goals, we have placed several GPS devices in seabirds of different species: the European shag (Gulosus aristotelis) and the yellow-legged gull (Larus michahellis) as part of the AMARYPESCA project, and the Audouin's gull as part of the GAUDIN project.

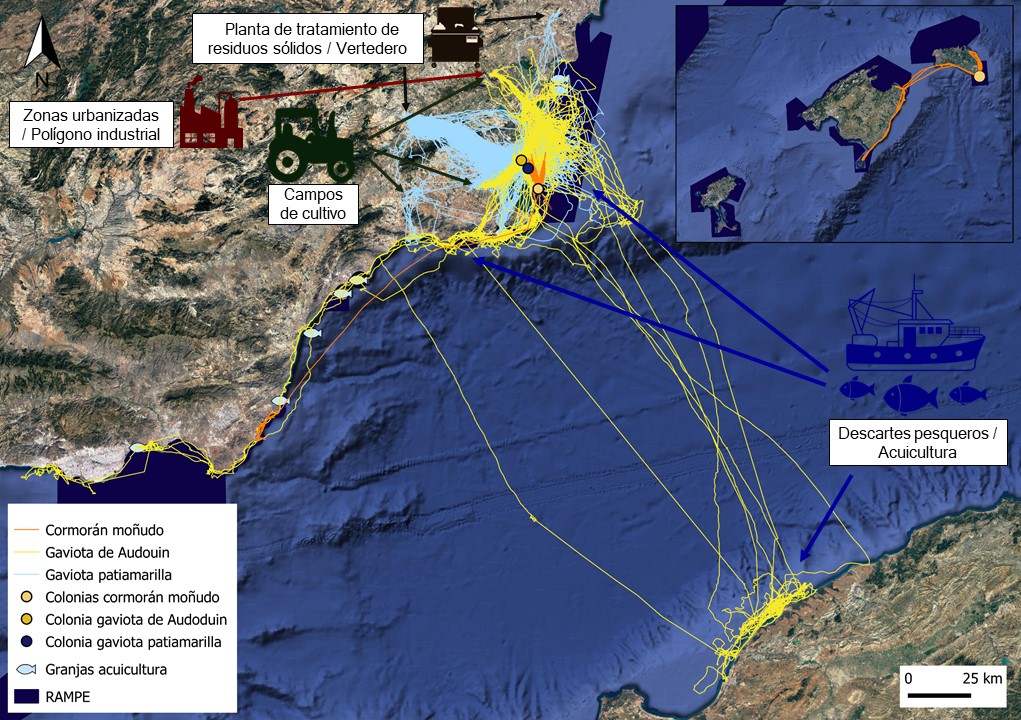

In the following map you can see the trips of all the individuals marked with GPS devices of European shag (orange) in Isla Grosa (Murcia) and Isla del Aire (Balearic Islands), and of yellow-legged gull (blue) and Audouin’s gull (yellow) in San Pedro del Pinatar (Murcia), registered from the time of its placement until the end of May.

Of the three species instrumented with GPS to date in the Spain’s east coast, we first worked with the European shag. This seabird, which nests in areas of rocky cliffs, is listed as a vulnerable species in the Spanish Catalog of Threatened Species, as it is threatened by bycatch, overfishing and marine pollution.

The ANSE team, partners in the AMARYPESCA project, carried out the fieldwork in January and February, deploying GPS devices in a total of eight adult birds, mostly breeders, from Isla Grosa (Murcia) and Illa de l’Aire (Balearic Islands).

European Shag (Gulosus aristotelis) equipped with a GPS/GSM device. Photography: ANSE.

The spatial ecology of this species is still quite unknown and we hope that the results we are obtaining with this project can contribute to its knowledge. On the map above you can see how Isla Grosa’s European shags often move north, approaching and possibly interacting with fish farms. Instead, we can observe that the individuals of Illa de l’Aire move near the coasts of the islet, as well as Menorca and Mallorca. Here you can see in detail the latest movements of individuals equipped with GPS devices.

Next, we worked with the yellow-legged gull, a seabird with mostly coastal habits, with great foraging strategy adaptability. Thanks to these generalist attributes, it has adapted in an extraordinary way to take advantage of trophic resources derived from human activity, such as the food they obtain from landfills or from fisheries discards. This association with anthropogenic habitats has made their populations grow exponentially throughout its range, and it has very abundant breeding populations throughout the coast. ANSE staff deployed 17 GPS devices in adult breeding individuals from San Pedro del Pinatar (Murcia).

Yellow-legged gull (Larus michahellis) equipped with a GPS device. Photography: Antonio Zamora.

The first results obtained support this change in diet towards anthropogenic food subsidies, mainly of terrestrial origin (landfills, waste treatment centers, crop fields and irrigation ponds ...). In addition, the trips they make at sea seem to be linked to possible interactions with fisheries discards and fish farms. Here you can see the latest movements of individuals equipped with GPS.

The last species we have worked with is Audouin's gull. This species is endemic to the Mediterranean, and cataloged as vulnerable in the Spanish Catalog of Threatened Species. The Spain’s east coast is home to the most important breeding populations of the entire species. Its main current threats are bycatch, dependence on fisheries discards and marine pollution.

A field team of people from ANSE and the University of Barcelona deployed seven GPS devices in breeding adult Audouin’s gulls from San Pedro del Pinatar (Murcia).

Deploying a GPS device (using a harness) on an Audouin's gull (Ichtyaetus audouinii). Photography: Raquel Castillo Contreras.

The results obtained so far demonstrate that this species also makes extensive use of land resources of anthropogenic origin, including those available in urbanized areas and cultivated fields. However, our preliminary results show that part of the population specializes in feeding in marine habitats, often taking advantage of fishing discards. Here you can see the latest movements of Audouin's gulls equipped with GPS.

Finally, it is worth highlighting the importance of these results, albeit still preliminary, towards the achievement of the objectives of both projects. A better understanding of the spatial ecology of seabirds and their interactions with fisheries and fish farms, and adding to the equation the limits of the current RAMPE, will allow us to understand the role that the current RAMPE has in the conservation of seabirds. This will help improve the management of RAMPE and of fishing and aquaculture production activities so that human activities and marine birds can coexist.