By Margarita Díaz-Andreu, Principal Investigator Artsounscapes and Neemias Santos da Rosa, Junior Postdoctoral Researcher.

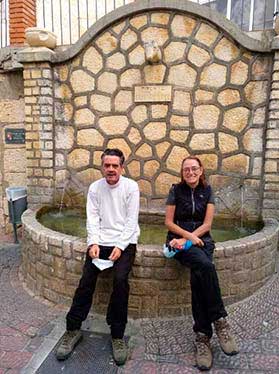

The Artsoundscapes Project was out in the field again from 5 to 13 October, albeit in this case it with only two members of the team, Principal Investigator Margarita Díaz-Andreu and postdoctoral researcher Neemias Santos da Rosa. It was a tight schedule that had taken weeks of preparation, as we were planning to visit a large number of sites in four different autonomous communities in Spain: Valencia, Castilla-La Mancha, Murcia and Andalucía. The purpose of this fieldwork was to identify and take some basic notes on various Levantine rock art sites in preparation for future acoustic tests once the necessary permits have been obtained. In this post, we will include some of the information already provided on our Facebook page at the time and also add some new details.

Ready to depart

Our intended route

Our trip began in Valencia, a city we reached by train. From there we drove to the Caroig mountains where we met rock art specialist Ximo Martorell. At the Abrigo de Voro site we were impressed by the large number of finely traced figures, including many female motifs and a group of four warriors that has been interpreted as representing a collective male dance. Some one hundred metres to the north we also visited Cuevecicas del Estiércol, a very long but narrow shelter with two small female figures. On the other side of the river we found El Garrofero, an easy-to-access shelter with the remains of a large female figure, possibly dated to the earliest period of the Levantine rock art tradition.

Abrigo de Voro

Scene interpreted as a collective dance at Voro

Female figure at Voro

Ximo Martorell showing Marga rita Díaz-Andreu some of the figures he has documented

Moving to the southeast, we crossed the border between the Valencian Country and Castilla-La Mancha autonomous communities en route to some of the best-known Levantine rock art sites. These shelters are at the eastern end of the province of Albacete and were discovered around a hundred years ago. The large number of painted figures in them inevitably drew the attention of the locals, who mentioned them to inquisitive archaeologists. Our visit included the Cueva de la Vieja in Alpera and the Abrigo Grande in Minateda, situated about a hundred kilometres apart. They have recently been re-examined by Anna Alonso, Alexandre Grimal and Juan Francisco Ruiz López. Both sites are in spectacular landscapes with magnificent views of the facing plain. They have an impressive thematic variability of images painted with remarkable technical skill. It was very interesting to note the local people’s pride in the paintings, which have been reproduced on a wall alongside one of the main roads in the village of Alpera. This pride is also found in other less politically correct places such as the toilets of the villages municipal cultural department headquarters, where primitive male and female figures indicate the “Ladies and Gents”. We found out later that the same resource had also been used at the Rock Art Interpretation Centre in Moratalla and in the local bar of Zaén de Arriba.

Views from the Cueva de la Vieja rock art shelter

The Cueva de la Vieja in Alpera and the Abrigo Grande in Minateda are not the only rock shelters in the area. Not far from the former, we went to see some smaller sites with the architect Chimo García and one of his relatives. These are considered minor sites because they have fewer figures and usually – although not always – have limited visibility.

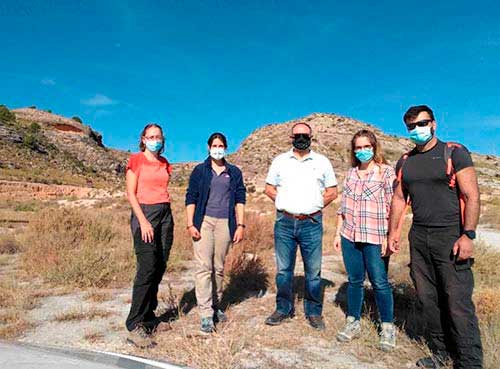

The group visiting the Abrigo Grande of Minateda

The Abrigo Grande is close to the hamlet of Minateda. In addition to the authors of this blog, the group visiting the site comprised local guide Gemma Ortiz and our friends from neighbouring Jumilla, Emiliano Hernández and Myriam Ruiz López.

View across the landscape

Female figure with child

The Cueva de la Vieja panel as reproduced in the village of Alpera

Neemias Santos da Rosa checking what has been published at one of the smaller sites. Chimo García is to the left of the photograph

Admiring the rock art at Minateda

A view of the impressive Abrigo Grande of Minateda

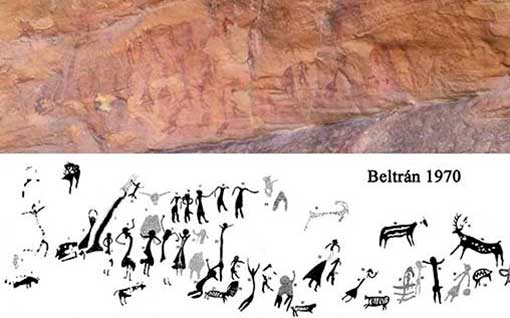

We often think we are going to remember how to reach a site. However, ten years after one of us had visited the Barranco de Los Grajos, it did not help that, unlike all the other municipalities we contacted in the four provinces, this was the only one that did not offer us any assistance. Unfortunately for us, the road that once approached the site was badly damaged and, rather than risk our lives trying to drive up it, we left our car in what we thought was an area near the sites. Now we laugh about our adventure on that day, but when we finally reached the small gorge, we were exhausted, hungry and thirsty. Sometimes, however, it is worth experiencing the terrain the way we did on that fateful day. The sites were as impressive as ever and through the fence we were able to see the dance scene at Los Grajos. Confusingly, while the shelter with the dance scene has traditionally been known as Los Grajos I (including in Alonso and Grimal 1997, Dams 1984: 162, Jordán 1995-96, Martínez Sánchez 1996, Montes & Cabrera 1991-92, Walker 2019), some archaeologists designate it as Los Grajos II (Lomba & Salmerón 1995, Lomba Maurandi 2018). We spent hours going through the bibliography before we realised this confusion.

View of the Grajos gorge with Shelters I and II

Dance scene at Los Grajos I

After Alpera, Minateda and Cieza we spent two days based in the village of Moratalla. On 8 October our guide was Esteban Silicia from Moratalla Town Council. We first drove to the hamlet (pedanía) of Benizar (if we can call a place with almost a thousand inhabitants a hamlet!). Not far away is the attractive Rincón de las Cuevas, where the rock art is indeed very difficult to see. However, the spiritual significance of the place can still be seen in a modern altar probably used for the romería (a sort of annual Christian pilgrimage common to most villages in Spain).

Rincón de las Cuevas at Benizar

We rounded off the morning by inspecting the sites of Molino de Bagil and the impressive shelters of Fuensanta before having a very late lunch with Enemérito Muñiz on the terrace of the local bar in Zaén de Arriba.

The modern altar at the site

We ended the day with visits to the Abrigo de Capel and, practically in the last light of the day, the fantastic group of La Risca sites, where we wanted to see the well-known female representations. These are two large, elongated female figures, the longest about twice the height of the one to its right, that can be seen in a niche three metres from the floor level. It is not that unusual to find representations of women in pairs, but the size of these is unique! The bibliography repeatedly mentions that they could be dancing and their similar postures may indeed indicate this.

With Salvador Ludeña in the area of the Abrigo de Capel

October 9 has been designated as European Day of Rock Art. It was on such a day in 1902 that Émile Cartailhac sent Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola’s daughter, María, a letter acknowledging his error when he had refused to accept the authenticity of the Altamira rock art paintings discovered by her late father. There were several celebrations in the six autonomous regions in the Levantine territory, including Murcia. These major celebrations were multiplied by events organised on a municipal level, such as in Moratalla. At 10 am, taking advantage of the short delay, we first briefly paid a visit to the tourist information office, where the female figures from La Risca I rock art shelter have been included in its logo. Soon after we were in front of the Town Hall where the mayor, surrounded by several councillors and the director of the Rock Art Interpretation Centre, gave a short speech in front of the cameras. We were later also interviewed and our presence was then noted in the local press: in newspapers – in El Diario and La Opinión –; and on the radio on Onda Regional.

Tourist Information Office at Moratalla

We were glad to see that the Rock Art Interpretation Centre was finally open after having been closed for years. It looked really great! We were shown round by its director, Salvador Ludeña, who also guides groups of tourists to visit the rock paintings

Event to celebrate the European Day of Rock Art

At the Casa de Cristo Rock Art Interpretation Centre in Moratalla

After this stopover at the interpretation centre, we visited many sites and observed scenes, superimpositions, colours, and so many other details that make Levantine paintings so intriguing. Sites such as the group at Fuente del Sabuco and Cañaica del Calar were on our list for that day, which finished in the peaceful, quasi-oasis-like hotel of Casa Pernías in the Campo de San Juan area.

Neemias Santos da Rosa taking notes at Cañaica del Calar

Casa Pernías

On 10 October we returned to the province of Albacete, this time to its southern end, to visit the grandiose rock art sites of Solana de las Covachas, Torcal de las Bojadillas and other lesser sites in the municipality of Nerpio. In the first two, together with Núria Álvarez – our guide from the Nerpio Tourist Office –, we noted that the acoustics properties of the shelters are undoubtedly interesting. The art is indeed magnificent. We were impressed by the human figures with what looks like eccentric hairdos and the many tiny figures that probably date from to the last phase of Levantine art. In the afternoon we had the honour of being guided by local expert Antonio Carreño, the driving force behind rock art research in this area for the last thirty years, together with his regular companion of at least two decades, Miguel Angel Mateo Saura.

Signpost at the entrance to the protected area of Solana de las Covachas

Female representation at Solana de las Covachas

Rock cliff where the Torcal de las Bojadillas shelters are located and the view from them

Antonio Carreño and Margarita Díaz-Andreu at one of the rock art sites visited in Nerpio

Part of the cliff where the rock shelters at Solana de las Covachas are located

Signpost at the entrance to the protected area of Torcal de las Bojadillas

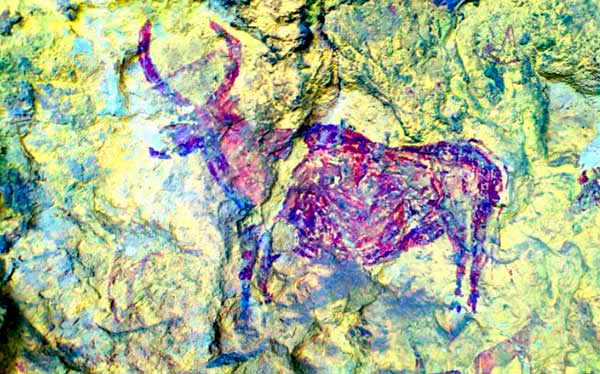

Female figure at Torcal de la Bojadillas with the uncommon eccentric hairstyle that is found in this area (Alonso & Grimal 1996: Fig. 166)

Boarding at the entrance to Nerpio stating that the municipality has 70% of the total number of rock art sites in Castilla-La Mancha

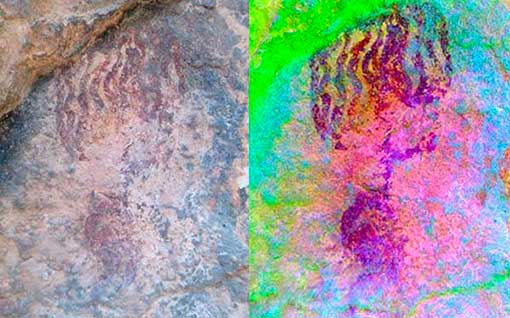

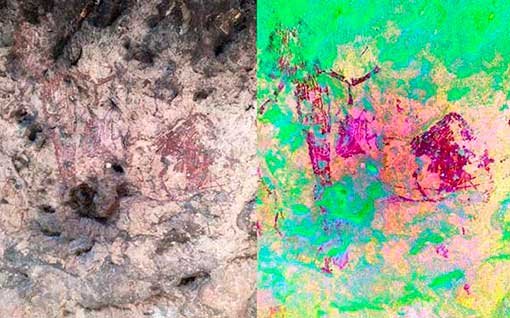

On Sunday 11 October, Antonio Carreño took us first to see the rock art site of Prado del Tornero, right next to the village of Nerpio. As at many other sites, the rock art figures have been largely lost, but they magically appear by applying the ImageJ software plugin D-Stretch to the photographs. Later, in Hornacina de la Pareja, after a steep climb, we were surprised by one of those motifs with the very unusual headdress that is only found in this area. Neemias and Antonio got into a debate as to how they were painted, the subject of Neemias’ recent PhD thesis. If Marga hadn’t intervened, we’d still be there, talking about all the minutiae of the chaîne opératoire related to painting Levantine rock art motifs, etc. Back in Nerpio, we finally said goodbye to Antonio and the Nerpio area.

Prado del Tornero (Nerpio)

Deer figure at Prado del Tornero

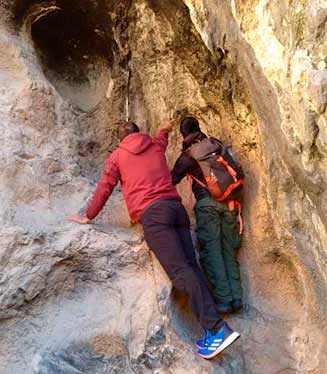

Climbing to reach the Hornacina de la Pareja shelter

Neemias Santos da Rosa and Antonio Carreño discussing how the paintings were made

Deer figure at Prado del Tornero enhanced with D-Stretch

Another female figure with the peculiar local headdress at Hornacina de la Pareja shelter

Antonio Carreño and Margarita Díaz-Andreu at Nerpio village spring

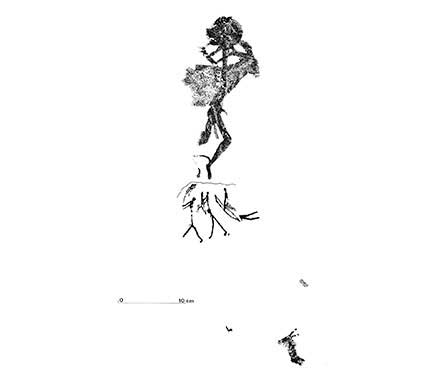

October 12 was a public holiday, but we decided to continue our tour and once again changed province and autonomous community by moving on to Jaen in Andalucía. Our local guide, Emilio, helped us find the Cuevas del Engarbo site and we marvelled at the figures we could see on the walls.

On the way back we saw wild goats and deer by the roadside. It felt like such a lost place, so far from anywhere!

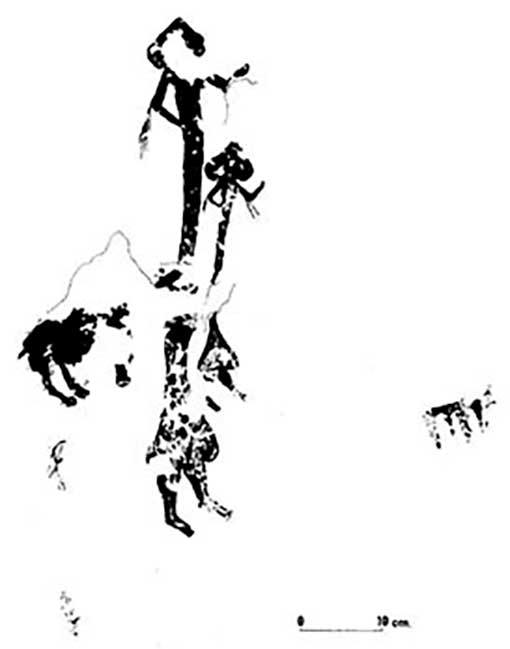

Cuevas del Engarbo rock art site

Documentation of some of the figures painted at El Engarbo I (Soria Lerma & López Payer 1999: Fig. 4)

Emilio and Neemias checking the rock art motifs at Cuevas del Engarbo

Mountain goat by the road

On our last day in the field we had Barranco Segovia on our list, a place so difficult to reach that, despite Juan Francisco Jordán Montes’s indications, we needed help, which we received once again from Enemérito Muñiz. At the site, we were surprised by the fantastic views and intriguing figures.

Shelter visited at Barranco Segovia (Letur)

Two figures. The one to the left is a female motif with a bag. The one to the right is incomplete

On our way back to Valencia, we stopped to have lunch with Emiliano Hernández, director of the Jumilla museum. We were and still are extremely grateful to him for all the help he offered us in organising this trip. Without him everything would have been much more difficult.

Having returned the car in Valencia, we then caught the train bound for Barcelona… After covering more than 2,000 kilometres on roads and trails, we can only say that we thoroughly enjoyed the expedition while, at the same time, we learned a great deal. We are now in a better position to arrange permits for acoustic tests and have many ideas that we hope to develop in the future.

Margarita Díaz-Andreu and Enemérito Muñiz

Painted bull figure at Torcal de las Bojadillas