By Diego Moreno

How does a sound and image engineer go from working with microphones and processing audio signals to walking 10 km a day with 15 kg of equipment on his backpack to measure sound properties of rock art sites?

This blog post focuses on the many challenges and wonderful places the Artsoundscapes team encountered on its latest fieldwork in South Africa in spring 2022, told through the eyes of an acoustic engineer surrounded by archaeologists.

The experience began, as always, at the Faculty of Geography and History in Barcelona, where we carefully prepared and packaged all the necessary equipment. This time, three team members went to the field: the Principal Investigator of the Artsoundscapes project, Margarita Díaz-Andreu, the postdoctoral researcher Neemias Santos da Rosa, and myself, Diego Moreno, as research assistant. It turns out that carrying a dodecahedron sound source, three microphones, audio cables, measurement laptop and batteries on three consecutive flights for almost 24 hours is quite exhausting. Fortunately, we all survived the ordeal and arrived safely at Pietermaritzburg’s small but quite charming airport. Here we were greeted by both rock art specialist Dr. Ghilraen Laue (KwaZulu-Natal museum curator) and archaeologist Chih-Jen Hung (or CJ, an MSc student, University of Witwatersrand), who would accompany, guide, and assist us during the fieldwork.

After dropping our bags at the hotel at Pietermaritzburg, we were given a tour of the impressive KwaZulu-Natal Museum, including its current exhibitions, repositories, storage, and offices. It certainly was a small taste of what was to come in the following days!

Early in the morning, the next day, we headed towards the first area where we would take acoustic measurements: Kamberg. After unpacking at our lodging, the Knackered Swan B&B, we checked and organized the necessary equipment for the first day of fieldwork.

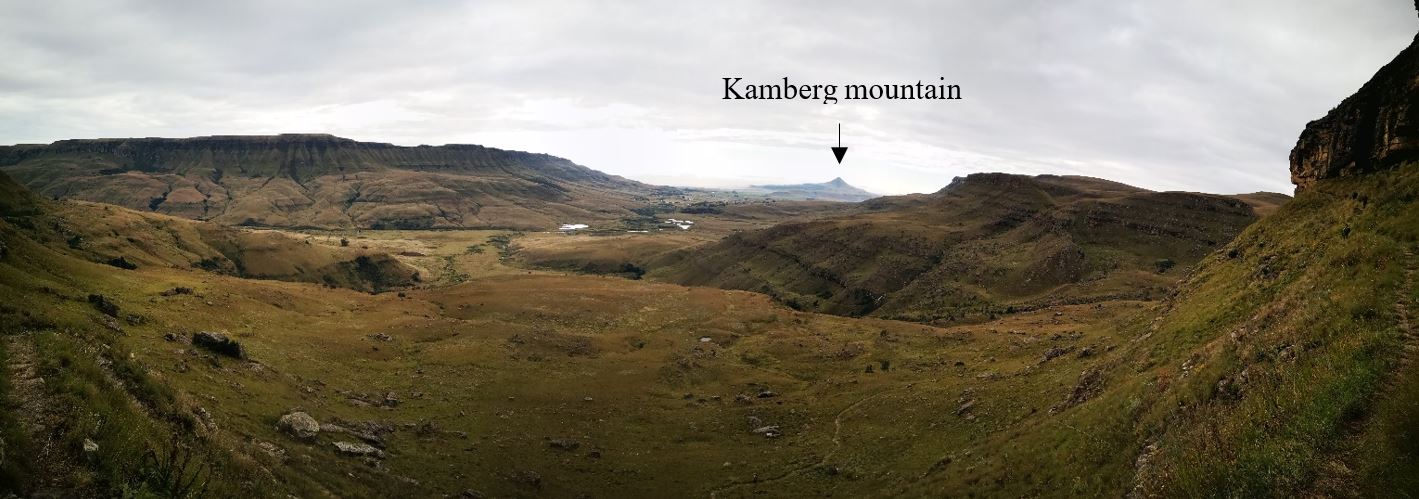

After a short drive through the countryside, we finally arrived at Kamberg Rock Art Center, located at the entrance of the Kamberg Nature Reserve to meet our two local guides: Richard Duma and Raphael Mnikahti. Apart from knowing the best routes to get to the rock art sites, they taught us some Zulu words, intaba (mountain), qaphela (danger), and that Kamberg – a fantastic mountain that is key to the understanding of the landscape in the area – comes from comb-hair, for this particular mountain has numerous folds if seen from a different angle. Right away the landscape felt breath-taking, and as we kept walking and ascending towards the first site, we could not help but fall in love with the magnificent mountains, streams, waterfalls and, as you’ll soon see, the rock art. We were also advised not to point to the Kamberg mountain, for it is said it brings forth rain. Foolishly, we somehow disregarded this advice, and the next day it started pouring!

Figure 1. Kamberg Rock art Centre, a stop in the middle of the trail up to Game Pass I (from left to right: Raphael, myself, Neemias, CJ, Richard and Marga, Ghilraen behind the camera); and a panoramic view of the landscape. © Artsoundscapes Project

After a good rest at the top of what is locally named krans (essentially a sheer rock face on a mountain), we witnessed one of the most beautiful rock art panels in the area at Game Pass I. Coming from an engineering background, my only contact with rock art thus far was at the Madrid National Archeological Museum, where a replica of the bisons of the so-called Hall of the Paintings of Altamira (Cantabria, Spain) can be found. Nothing to do with the bisons, but needless to say that the rock art at Game Pass was an unparalleled first sight that I will remember forever.

From my limited understanding and what I learned from my colleagues, the rock art was made by the San-Bushmen that inhabited the region before they were either wiped or driven out in a recent period. Although their exact age is quite difficult to determine, they are estimated to have been produced over the past three millennia. Despite their age, what shocked me the most was the sheer amount of care, realism and technical detail they portrayed into the paintings. The use of colours, precisely contoured shapes, and of perspective in dancing and hunting compositions does nothing but reinforce this idea that the San-Bushman artists were masters of their craft. As for the motifs, they mainly depict human and animal figures, with the sacred eland antelope (that, to this day, roams the plains) as the most recurrent shape

Figure 2. Ghilraen, Marga, myself and CJ, at Game Pass I main panel (top left); general view of Lonyana shelter (top right); trance scene, Lonyana shelter (bottom left); Rosetta panel (Game Pass I), where a shaman is touching an eland and acquires some of its properties. © Artsoundscapes Project

We visited a total of 18 shelters in the Kamberg area, making the decision to measure 13 of them in accordance with their ideal conditions related to space, weather conditions and high levels of ambient sound that would allow reliable final results. In each of them, we gathered multiple impulse responses, we recorded some minutes of ambient sounds and, of course, we took many amazing photos both of the site itself and the surrounding landscape. This would not only allow us to analyse the sonic properties of the sites, but also categorize sound sources and study how we humans perceive them. As you can see in the next images, the essential tasks of levelling the tripods and taking precise measurement of distances to the floor, walls, and between sources and receivers were given careful consideration in order to ensure good intercomparability. In addition, we put special care in avoiding water drops and in reducing the risk of tripping and equipment falling due to the irregularities of the surfaces.

Figure 3. Some images of the team doing acoustic measurements and photographic documentation at Pluto I (top left), Game Pass I (top right); Willem I (bottom left) and Pluto III (bottom right). © Artsoundscapes Project.

One of the last days in Kamberg we conducted an interview with one of our guides who is an elder of the nearby village, Richard Duma. He spoke about his work of bringing together modern San descendants to keep and preserve their traditions, and he expressed his thoughts about what makes the sites special nowadays for him. He also hypothesized on what elements of the space could have inspired San ancestors to paint where they did. We later found that he has been interviewed in other occasions! As Michael Francis explains, he and his family identify themselves as Abatwa, the Zulu word for ‘Bushmen’ (2009a, 2009b).

As I pleasantly discovered, archaeological fieldwork is a breeding ground for anecdotes: the second day we were forced to go back to the car in a thunderstorm completely soaked; we often packed quickly because of incoming rain; sometimes we fell into rivers, encountered baboons, elands and enjoyed a day processing data by the fire at our resting place while it rained, since recording was not possible. We even found some rock art which was not documented when looking for sites with no paintings! I wonder then just how many sites are waiting to be discovered in such a vast landscape.

Figure 4. A herd of the wild eland that is depcted in the rock art panels (top left); baboons watching over us by the mountains (top right); Ghilraen at the newly discovered site dubbed Game Pass V (bottom left); and a group picture of the team. © Artsoundscapes Project

Alas, on the 1st of May, our time at Kamberg was over, and we moved to Giant’s Castle game reserve after saying goodbye to Richard, who stayed in his village. Margarita Díaz-Andreu also had to leave the field at this point to come back to Barcelona to receive the Spanish Menéndez Pidal National Award 2021 in the Humanities. We were all very happy for her, and proud that one of the reasons she had been granted such a prestigious award was because of her work in archaeoacoustics”

Giant’s Castle, being a tourist resort, is an area much more visited by the public, and it sports a whole range of cabins and lodges for events, trekking routes and, in general, leisure activities.

In general, in this new area the trekking to the sites was much less intense, as some of them were just on the side of the camp, easily accessible on foot, with paved tracks to approach them. However, this came at the cost of some unwanted modifications of many of the sites, such as boardwalks, and what seemed to be a recycling plant close to one of the sites (luckily, not too close enough). Accessibility had also had an adverse effect in the sites, for some displayed modern graffiti next to the original paintings which, in my opinion, somewhat ruined the immersion in comparison with the completely natural, mostly untamed landscapes of Kamberg.

As for the style of the paintings, we found them to be quite similar. There we also found the representation of animals and humans (or zoomorphs and anthropomorphs, in archaeology’s jargon), but with more common appearances of abstract figures and animal-human hybrids, thus reinforcing their shamanistic significance. This can be appreciated in the photographs we have selected to show this.

Figure 5. A small selection of the wonderful rock art of the Giant’s Castle area. From left to right, Camp Shelter (snake with eland head), Main Caves North (Small and large humanoids with eland heads and bags), and Wilcox Shleter (figure with strange features, bow and arrows). © Artsoundscapes Project

Technically speaking, this second phase of the fieldwork in Giant’s Castle shared many of the limitations encountered in the Kamberg area, although to a lesser extent, as the sites visited were much more open and spacious. In addition, favourable conditions and general ease of access to the area facilitated the measurement campaign significantly, reducing travelling time and increasing the rate of sites visited per day. Some of this extra time was used for the testing of a new microphone recently acquired by the project, the SennHeiser Ambeo microphone, in one of the sites. This microphone allowed us to record spatial impulse responses synchronously, and the viability of its integration on the measurement chain was assessed and considered valid for future use. In total we managed to visit 20 more sites, opting to measure 18 of them. We followed the same criteria and methodology as in Kamberg, making sure the distances were similar at least on one reference position of about 5 metres from the source. Some large sites such as Wildebeest Shelter on the photo below allowed quite a bit more freedom of movement, where we could easily reach up to 10 meters of source-receiver distances.

Figure 6. The team taking acoustic measurements at various shelters in Ginat’s Castle: Wildebeest shelter and Two Dassie I. © Artsoundscapes Project

A few more fieldwork curiosities, now referred to the Giant’s Castle area. We met some animals. The first to mention are snakes: even though Neemias was warily looking for them – his experience of doing fieldwork in Brazil has made him acutely aware of how dangerous they may be – we strangely found only a baby puffadder (well… apparently even more dangerous than adult ones!). We also encounter more amazing elands and especially bold baboons. You might think the baboons should be scared of humans but they are not! If in Kamberg we had seen him up in the mountains spying on our movements, in Giant’s Castle they naughtily pried around our cabins. They even managed to enter in Ghilraen’s cabin twice, opening doors, drawers, and making a complete mess! We certainly made sure not to go out with any food in our pockets and properly locked our doors after that!

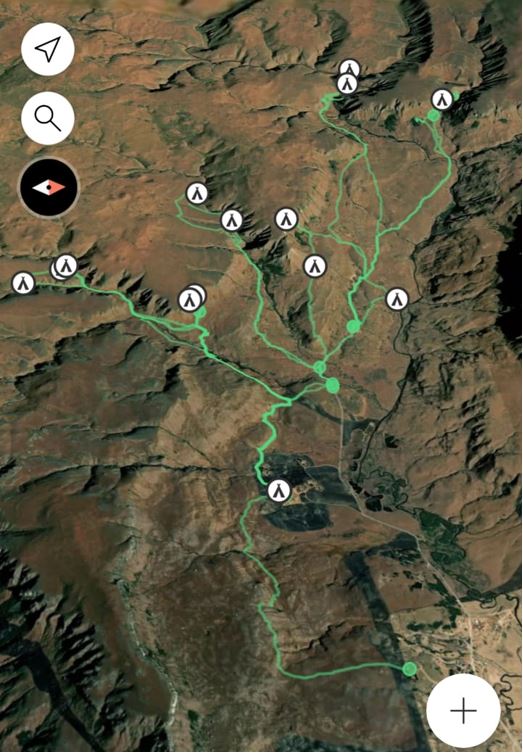

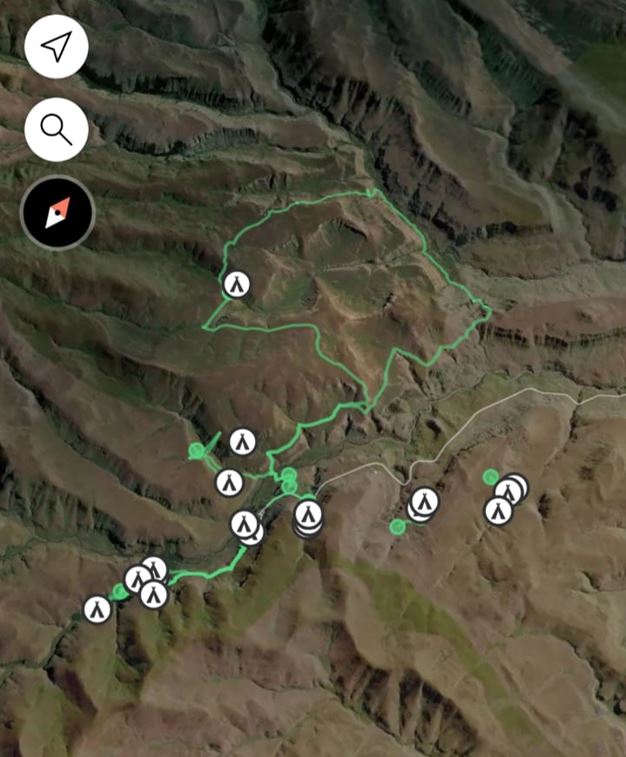

After almost getting lost the last day trying to find a site, reaching the 120 km mark in our pedometer app, having recorded a total of 32 sites and with a South Africa raw data folder in our laptop reaching the staggering amount of 85 GB, it was finally time to come back home. Although I was a little sad that our adventures were over, I looked forward to some well-earned respite and to explaining about my own sort-of-Indiana Jones experience to friends and family

Figure 7. Our routes through Kamberg (left) and Ginat Castle (right). Each tent represents a recorded shelter. © Artsoundscapes Project

We first said goodbyes to our good friend Raphael Mnikahti, who had accompanied us from the beginning of the trip as a guide. Once in Pietermaritzburg, Ghilraen invited us to her house for a braai (south African barbecue) to celebrate the success of our magnificent fieldwork and collaboration effort. It truly was a South African complete experience, including being subjected to one of their famous controlled power cuts known as load shedding!

On May 13th, it was time for the last goodbyes, first to Ghilraen, who very kindly took Neemias, Chih-Jen and myself to Pietermaritzburg airport. Then at Johannesburg airport where we said farewell to CJ. After another two travel legs and almost a day of being stuck in a flying metal container, we arrived to Barcelona, where we took the equipment back to our offices and went our separate ways for a well-deserved rest.

As a final note, both in my name and that of the Artsoundscapes project. I want to express my deep gratitude to every member that participated in one way or another during the fieldwork: to Marga, for giving this humble junior acoustician the opportunity to work with such a great team; to Neemias for being both the most tough and caring adventures and office companion; to Lidia for her invaluable remote advice and technical support during the fieldwork; to Ghilraen for being such a wonderful host, sketch maker and light-hearted soul, even when we seemed a bit lost; to Chih-Jen/CJ for his diligence, humour and mastery of setting up the tripods levelled; and to Raphael and Richard for teaching us so much about their culture and welcoming us crazy researchers with open arms.

To all of you, thank you for such an unforgettable experience!